Veterinary college students help provide safe, affordable spay/neuter services to help end pet overpopulation in Southwest Virginia

October 12, 2022

There is an intense focus, but also cheerfulness, amid the whir and hum in the operating room at the back of Mountain View Humane Spay/Neuter Clinic in Christiansburg, Virginia.

Dogs and cats have been brought by clients, by shelters and by the regional Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) for low-cost spay and neuter surgeries, performed by Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine students under the supervision of faculty.

“That’s why there are a million human beings here,” says Meghan Byrnes, clinical assistant professor for Shelter Medicine and Surgery, donning her orange and maroon Virginia Tech surgical cap, overseeing the scene around her.

Well, it’s actually just eight students, supported by two veterinary technicians and two faculty members. The students are on their final week of a three-week rotation in shelter medicine and surgery, a required clerkship for each veterinary student amid the 17 clerkships they complete over the final two years of their studies.

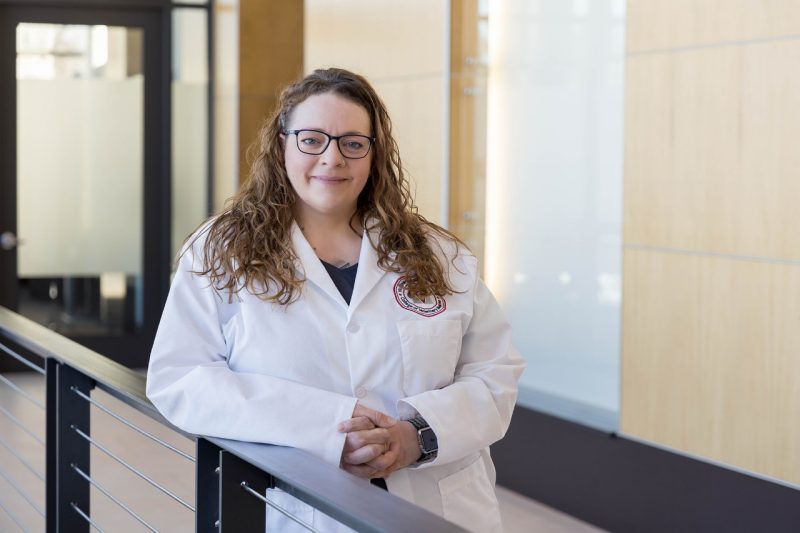

“We all enjoy what we’re doing,” said Madi Braman, a fourth-year veterinary student from Williamsburg, Virginia. “We’re happy and proud for what we’re doing for the community. It’s very fulfilling.”

For the community, the students provide inexpensive spaying and neutering, which help keep the animal population from escalating beyond the levels that can be handled by adoption into homes.

Various animal welfare organizations point out that a single unspayed female dog or cat can lead to tens of thousands of new dogs and cats, descendant generations left unchecked, within a few years.

“The dogs and cats come from clients, shelters and rescues,” Byrnes said. “Some of the cats are community cats,” she added, a term used to describe cats without specific human owners who wander free.

The surgeries can also improve pets’ longevity and owners’ time to have their companionship.

According to the Humane Society of the United States, studies conducted by the University of Georgia and Banfield Pet Hospitals showed that neutered male dogs live 13.8 percent to 18 percent longer and spayed female dogs lived 23 percent to 26.3 percent longer, on average, than unaltered pets.

“Being a nonprofit, we want to make sure everyone is able to afford quality pet care,” said Sylvie Peterson, executive director of Mountain View Humane Spay/Neuter Clinic. “One way to be resourceful is by providing high quality and affordable spay and neuter service, to prevent pet homelessness before it starts.”

The students, in return, get an opportunity for hands-on learning about how to perform soft-tissue surgery.

“For some of the students, this is the second surgery they’ve ever done when they get here,” Byrnes said. All have completed a second-year surgery lab and some, but not all, have had additional surgical experience in externships prior to the shelter clerkship.

“I’d never done a neuter prior to this rotation, now I’ve done 10,” Braman said. “This rotation teaches you all the tips and tricks to handle a spay on your own out in practice.”

Sophie Strome, a fourth-year veterinary student from Baltimore County, Maryland, said she had gained so much surgical experience in the shelter clerkship that she will be able to perform them in her next clerkship under the supervision of veterinarians at a small animal general practice in College Park, Maryland.

“I love this rotation, everyone is so kind,” Strome said. “They hold your hand but they give you the opportunity to learn and try new things. You have the opportunity to grow, you don’t feel judged, you don’t feel shamed.”

Strome’s ultimate ambition is to work in pharmaceuticals, but she wants to go into general practice first, and the shelter surgery clerkship provides much-desired experience.

The Mountain View Humane clinic isn’t the only one where VMCVM students perform spay and neuter surgeries. They do the same at Pulaski and Montgomery county animal shelters.

“One of the great things about this program is we go to different places,” Byrnes said.

Jill James, a shelter volunteer from Roanoke, supports the veterinary college students by making cloth surgical caps for the students, a practice she began during the pandemic when supplies were running short. She also washes the voluminous laundry dirtied at the shelter and sterilizes surgical instruments.

“I think what they do is so important,” James said. “Spaying cats and dogs, stopping pet overpopulation, lowering the cost so people can conscientiously have pets and take care of them and they might not be deterred by the cost. … And the fact that they can do this under wonderful supervision from these doctors at Virginia Tech. … Every one of the students I talk to is so enthusiastic.”