New animal behavior course helps students discern what dogs tell us without words

October 26, 2022

The “Paw Patrol” and other animated dogs may be able to speak fluent English, but in real life, dogs communicate to us with more subtle behavioral cues

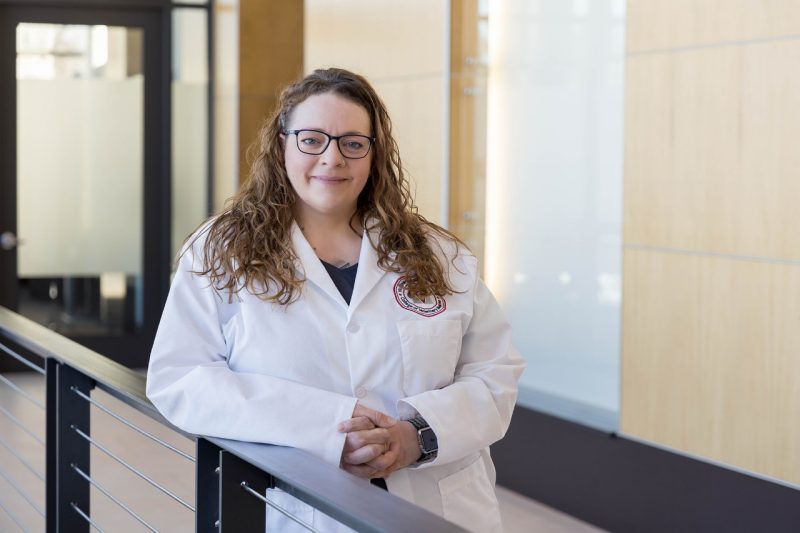

“That’s the only way they can communicate to us that there’s a problem,” said Virginia Buechner-Maxwell, who is coordinating a new course designed to help veterinary and animal behavior students identify those signals that could indicate more serious physical problems.

Some dog behavior signals can be obvious to any dog owner, Buechner-Maxwell said, such as a dog licking its paw indicating a wound. But other things might not be as obvious.

“If you have a nice dog and it suddenly becomes a bit aggressive, that can be related to some pain that is undiagnosed, and it’s a sign it probably should be seen by a veterinarian,” Buechner-Maxwell said. She also noted a behavior known as “stargazing,” when a dog looks up continuously, which she said research has linked to digestive problems.

Buechner-Maxwell, a professor and specialist in large animal internal medicine at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine and also certified in shelter medicine, and Erica Feuerbacher, associate professor of animal science and welfare in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS), together coordinate the new Companion Animal Behavior and Socialization course.

It’s an elective course offered to third-year students at the veterinary college, along with students in the master of public health program, and seniors and graduate students in animal behavior science through CALS.

“Dr. Buechner-Maxwell and I have collaborated on a variety of projects and we both have a huge interest in animal welfare,” Feuerbacher said. “Dr. Buechner-Maxwell really started the momentum for this class, and, because of my background as a professional dog trainer and my current appointment working in applied animal behavior, she was generous enough to invite me to collaborate with her on this.

“The curriculum is really a union of her expertise and my expertise. She taught lectures on animal health and how it intersects with behavior, and I taught lectures on the principles that impact animals‘ behavior.”

The course consists of eight live or recorded lecture sessions, five laboratory sessions working with Animal Care for Education (ACE) dogs, and two student presentation sessions. The 32 ACE dogs come from regional shelters, fostered by the veterinary college from August to mid-October, before being adopted into homes.

A major objective of the course is for students to learn how to recognize and understand behavioral cues that could indicate more serious physical problems in companion animals.

Socializing the dogs and helping them grow into behavior patterns that make them more desirable for adoption are also important aspects of the course.

“My goal is also for students to learn how to manage behaviors that owners might really find undesirable,” Buechner-Maxwell said. “It might not be abnormal, but might be irritating enough to an owner to cause them to break their relationship with the dog.

“This course I hope will help our students, when they’re out in veterinary practice, provide better options than just getting rid of your family pet.”

Third-year veterinary student Caroline Dwivedi of Annapolis, Maryland, has already seen the need for that behavior modification with an externship in a veterinary office.

“I worked in general practice and saw lots of behavioral issues the vets had to deal with and give advice on, and refer to behaviorists,” Dwivedi said. “I thought it would be a good skill to have for practice.”

Alex Tolleson of Richmond, Virginia, working alongside Dwivedi with Ruth the bloodhound on a pleasant October evening on the veterinary college grounds, also took the course to increase her knowledge in assessing and modifying dog behavior.

“I didn’t really have that much experience training or socializing dogs, so I figured this was a good opportunity to learn that, because that’s a skill you need for every dog, “ said Tolleson. “Every dog that comes in has to go through that process.”

Working with dogs previously housed in shelters means that students and the instructors often know little about each dog’s history and prior behavioral influences, which can create some unexpected challenges in the class.

“For me, previously I’d worked with service dogs, mainly Labrador retrievers, so this was a little bit different for me to work with shelter dogs, which are a variety of breeds, a variety of sizes,” said Rebecca Thompson of Pembroke, Virginia, a Ph.D. student in animal behavior and life sciences at CALS.

Feuerbacher said that the course serves as an introduction to principles of animal behavior for veterinary students, while the animal science students from CALS learned more about animal health and how it affects behavior.

“The students all did amazing in the course – you could see huge improvements in their training skills and that was reflected in the improvement in their dogs’ behavior,“ Feuerbacher said. “I was honored to get to collaborate with Dr. Buechner-Maxwell on this course and it was a thrill to work with all of the students and see how committed they were to helping improve their dogs’ lives.”