Virginia Tech researcher to test vaccine for norovirus

July 28, 2022

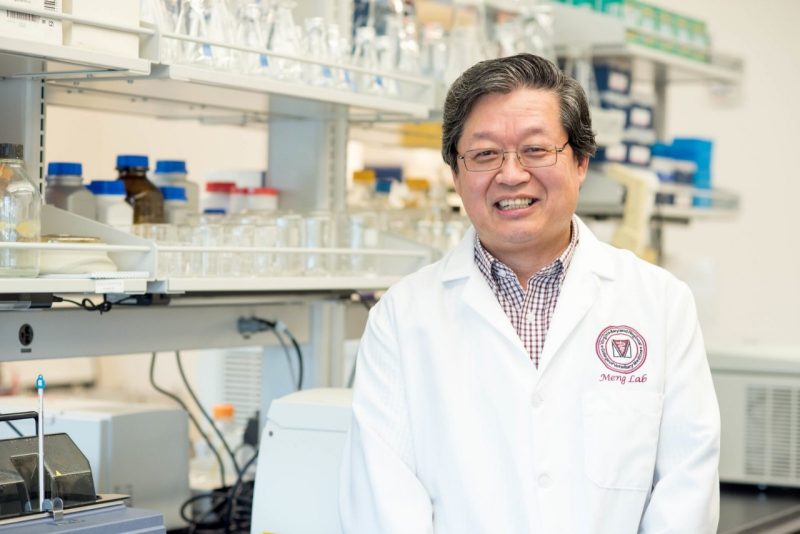

Lijuan Yuan, PhD, ProfessorVirology and Immunology, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology, VA-MD College of Veterinary Medicine,

Lijuan Yuan, professor of virology and immunology at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine at Virginia Tech, will evaluate a potential live oral vaccine for norovirus, the No. 1 cause of foodborne illness.

Indiana University’s John Patton and colleagues are developing a norovirus vaccine that uses the Rotarix rotavirus vaccine as a platform. Using reverse genetics, they will insert a norovirus protein into Gene 7 of the rotavirus. The virus will then express the norovirus protein in the gut, inducing an immune response against norovirus.

Yuan’s lab will evaluate the replication capacity, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy of the vaccine using gnotobiotic pig models of human rotavirus and norovirus infection and diarrhea. A gnotobiotic animal is one that has been specially raised to contain zero germs or bacteria so researchers can better study the effects of bacteria and viruses such as rotavirus and norovirus.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, norovirus is the leading cause of vomiting and diarrhea from acute gastroenteritis in the United States, resulting in 19 million to 21 million cases every year.

Norovirus tends to affect young children and the elderly the most. It’s responsible for about 24,000 hospitalizations and 925,000 outpatient visits for American children each year, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Rotavirus also causes acute gastroenteritis and hits young children the hardest.

"Together, rotavirus and norovirus cause over 415,000 deaths every year, and norovirus also has a very significant burden even in the countries that don’t have a lot of deaths. The economic cost is huge, $4.2 billion in direct costs and $60 billion in indirect societal costs. You hear about norovirus outbreaks on the news all the time in hospitals, nursing homes, and cruise ships and how it's closing down restaurants, so it's got a lot of economic implications,” said Yuan.

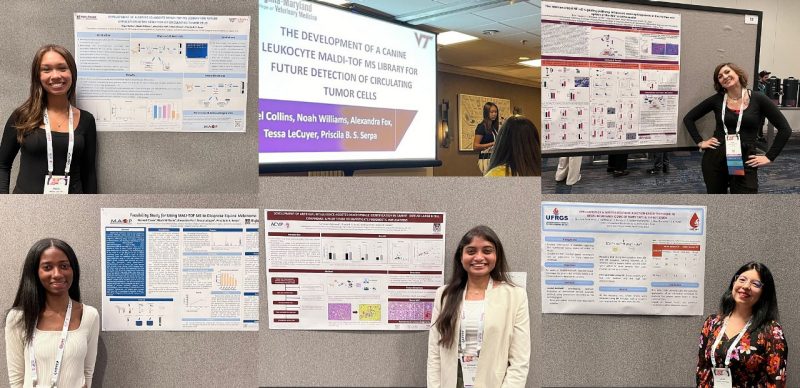

The Yuan Laboratory team, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology, Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine. Photo by Andrew Mann for Virginia Tech.

Unlike norovirus, there are multiple rotavirus vaccines available. It’s estimated that in the United States alone, rotavirus vaccination prevents 40,000 to 50,000 hospitalizations among infants and young children every year.

Why has it taken so long to develop a norovirus vaccine? Unlike many other viruses, norovirus cannot be cultivated efficiently in cell cultures. An added challenge is testing vaccines with animal models. For example, mice get murine noroviruses, which do not cause the same disease as noroviruses in humans.

"We will use a gnotobiotic pig model of human norovirus infection and diarrhea. It's actually the only laboratory animal model available that develops norovirus gastroenteritis that are similar to what you see in humans,” said Yuan.

The pig model is a unique one, as there are fewer than 10 gnotobiotic pig facilities in the country.

In her lab, Yuan studies gnotobiotic pig models of human enteric virus infection and disease, including how probiotics affect immunity and the evaluation of rotavirus and norovirus vaccines and anti-norovirus biologicals.

Working with gnotobiotic pigs is both time and labor intensive, but the pig model of norovirus will test a vaccine that could help millions of people.

Written by Sarah Boudreau