Virginia Tech veterinary college gets funding for research into parasite found in cats

August 8, 2022

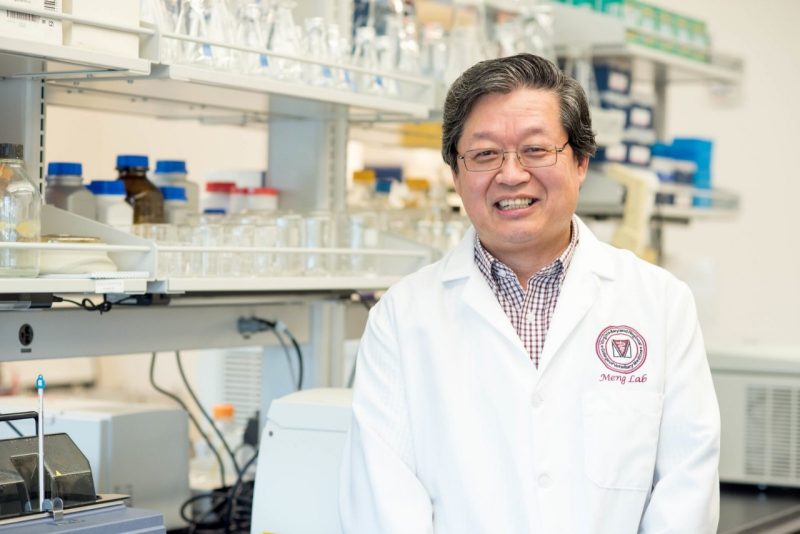

The Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology team is led by principal investigator assistant professor Raj Gaji

Found in cats, Toxoplasma gondii is a human pathogen with serious health ramifications, causing life-threatening illnesses for people with immunodeficienies, miscarriages in pregnant women, and blindness in newborn children. A National Institutes of Health grant awarded to the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine will fund a two-year study to understand treatment options better.

Researchers in the Department of Biomedical Sciences and Pathobiology will explore the function of a novel tyrosine kinase-like (TKL) protein in Toxoplasma reproduction. The goal is to reveal the role of this parasite protein in cell division and identify its signaling network, which could open doors for new treatments and care. The team is led by principal investigator and Assistant Professor Raj Gaji with assistance from Associate Professors Tom Cecere and Shannon Farris.

"Toxoplasma gondii has an interesting life cycle in that it undergoes its sexual reproduction only in cats," Gaji said. "Humans can pick up the parasite through contaminated water and meat or placental transmission during pregnancy. If farm animals consume the pathogen — such as water contaminated with cat feces — they develop cysts in their muscles. If people consume uncooked meat, they can pick up the infection, and if a woman is pregnant, the pathogen can be transmitted to the fetus. In the U.S. studies show that about 10 to 15 percent of the population (40 million people) are infected with the parasite, but their healthy immune system stops the parasite from causing illness."

When Toxoplasma gondii gets into the human body, it replicates and travels through the bloodstream to reach different organs including the brain. The infected person may experience mild symptoms such as fever during initial infection. But once the immune system kicks in, the parasite changes form and forms cysts mainly in the brain.

"So far, although the initial infection can be treated using two drugs, once the parasite spreads through the blood and into organs, there's nothing we can do. There's no drug to treat the form that stays in the brain because the parasite isn't responding to any treatment," Gaji said.

This means the person is infected for life. The parasite will stay dormant in the brain with no complications if the individual is healthy and their immune system is functioning well. Unfortunately, the same isn't true for more vulnerable populations.

"If an individual's immune system is compromised, the parasite can reactivate and it's incredibly destructive. It can cause sudden death in patients with infections like HIV or cancer patients undergoing organ transplants, and it can also lead to miscarriage in pregnant women and blindness in newborns," Gaji said.

The grant will allow Gaji and the team to use mass spectrometry analysis to understand the roles of this TKL protein in Toxoplasma gondii development. Identifying and understanding key proteins involved in developing and progressing Toxoplasma gondii infection is necessary for developing new treatments.

Gaji added, "Studying this parasite is important because the current drugs treating acute infections have several toxicities. There's no vaccine to prevent the infection and protect pregnant or immunocompromised individuals. We must keep working on new drugs to effectively kill this parasite and develop safe, effective methods for treating toxoplasmosis."