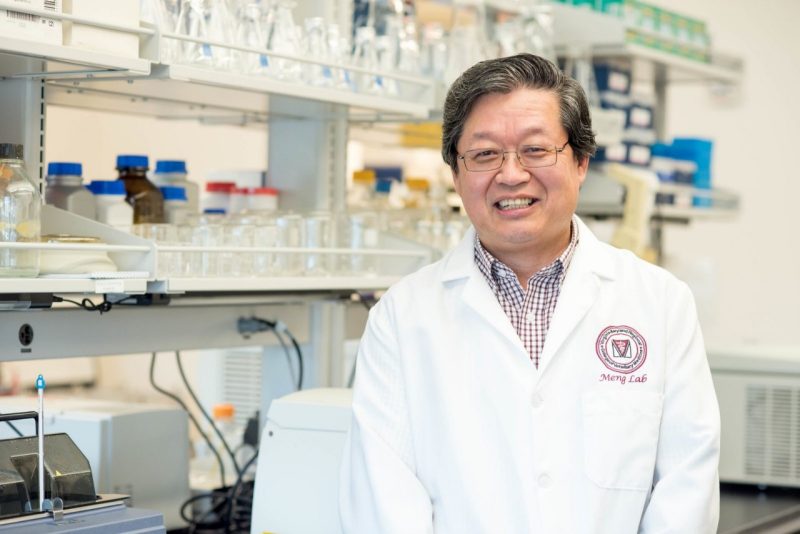

X.J. Meng awarded $2 million NIH grant to study hepatitis E-related neurological disorders

December 11, 2023

The first four letters of the alphabet often get more attention when it comes to hepatitis, but hepatitis E is a growing human health risk.

X.J. Meng, University Distinguished Professor of Molecular Virology in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, is the principal investigator for a $2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study neurological inflammation and complications from hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection.

With continuous funding from the NIH since 1999, the Meng Lab at Virginia Tech has for many years studied various aspects of the hepatitis E virus and how it infects animals and humans.

The “other” hepatitis

“Hepatitis E is an underdiagnosed disease in the United States,” said Meng, also a professor of internal medicine at the VTC School of Medicine. “We don't have an FDA-approved diagnosis test for hepatitis E here in the United States, so patients with hepatitis are not routinely tested for hepatitis E. If you're not looking for it, you’re not going to find it.”

Most people who acquire the hepatitis E virus, commonly through drinking feces-contaminated water, exposure to infected animals, or consumption of undercooked animal meats, never know they have it. Most do not have symptoms or only have self-limiting mild-disease and do not seek medical intervention. But for immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women, the disease can be deadly.

Annually on a global scale, there are 20 million hepatitis E virus infections in humans, leading to 3.3 million cases of disease and 44,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. The mortality rate for pregnant women with hepatitis E can be as high as 25%. The majority of immunocompromised individuals infected with HEV will progress into chronic hepatitis with severe liver damage.

“Hepatitis E is most common in developing countries with inadequate water supply and poor environmental sanitation,” the WHO reports. “Hepatitis E epidemics involving large numbers of people have been reported in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Central America.”

Meng said prevalence of the disease has been increasing in some industrialized countries, particularly in Europe likely because some pork products are being consumed not fully cooked. Pork is the major source of foodborne hepatitis E.

The disease has been rare in the U.S., but one study testing the blood of veterinarians who worked with pigs showed that as many as 35% had developed antibodies against the hepatitis E virus, signaling a prior infection.

The study

Beside hepatitis disease HEV infection is also associated with a wide range of neurological disorders, including Guillain-Barrê syndrome and neuralgic amyotrophy. More than 5% of infected patients developed neurological complications, but how and why these neurological conditions occur remain a mystery.

The Meng Lab’s research supported by this grant will focus on understanding how the hepatitis E virus affects the cells in the neurovascular unit, leading to neurological injury.

“We think that the virus infects some of the cells in the neurovascular unit,” said Meng, who is also affiliated faculty of the Center for Emerging, Zoonotic and Arthropod-borne Pathogens at the Fralin Life Sciences Institute. “Normally those cells are immune-privileged, as part of the blood-brain barrier to limit the entry of pathogens, immune cell and mediators to the central nervous system.”

The host’s immune system releases cytokines in response to the infection, but certain cytokine responses can cause cell death and tissue damage, Meng said. He believes that it’s those inflammatory responses from HEV infection that may be associated with neurological injury.

“We expect to identify HEV-specific neuroinflammation and neurological lesions and types of neural cells involved in neuroinflammation,” Meng said, “and we also expect to delineate the underlying molecular mechanisms of HEV-mediated neuroinflammation.”

If the mechanisms of hepatitis E virus-associated neurological disorders can be found in the laboratory, therapeutics such as inhibitors or antivirals may be developed to prevent or threat the neurological complications.

Co-investigators for the grant include: Debin Tian, research scientist in virology; Wen Li, research scientist in neuroscience; and Tanya LeRoith, clinical professor of anatomic pathology. Other key personnel for the project include Hassan Mahsoub, senior research associate in virology; and Lynn Chandler, senior laboratory specialist.

Circling back for Meng

While working at the NIH in the 1990s, a veterinarian presented Meng with cases of unexplained pathological liver lesions on pigs for him to study.

“Some of those samples came up positive for hepatitis E virus, and I was baffled,” Meng said. “At that time, the hepatitis E virus was not known to be prevalent in the United States, we thought this was only in developing countries. So, after extensive studies, we ended up discovering the first animal hepatitis E virus from pigs in the U.S., which we named the swine hepatitis E virus or swine HEV. It can also infect humans.”

Subsequently, the Meng lab also discovered avian hepatitis E virus in chickens in 2001. Since the initial discovery of swine HEV in 1997, the virus has now been identified from more than a dozen animal species. Hepatitis E is now a recognized zoonotic disease, as strains of the virus from pig, rabbit, deer, and rat can also infect humans.

Not only will Meng again be studying the zoonotic virus he discovered, but also, that discovery while at NIH led his career toward the veterinary college despite his human medical training, and he is now the recipient of another NIH grant.

“After I finished up my training at NIH, I decided to work in a veterinary school because the virus naturally infects large numbers of animals and can jump species to infect humans,” Meng said. “I thought the veterinary school would be a better home for me. It was a serendipitous discovery that led me to work on zoonotic pathogens that affect both humans and animals.”