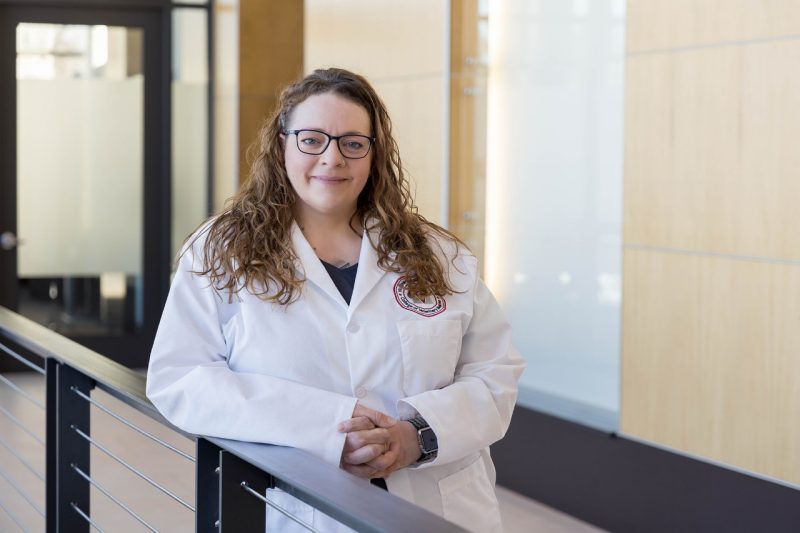

Outstanding Doctoral Student Allie Kaloss talks about life as a Ph.D. student and looking forward to joining the DVM Class of 2027

May 5, 2023

This year's outstanding doctoral student for the veterinary college is Alexandra Kaloss. A DVM/Ph.D. student, she is currently finishing her four-year Ph.D. before starting the DVM program this fall in the Class of 2027.

So please tell me your name and what you're doing right now.

I'm Alexandra Kaloss. I am a fourth-year DVM/Ph.D. student in Dr. Michelle Theus' lab. What I'm doing right now is preparing my dissertation on ischemic strokes.

What are ischemic strokes, and why are these your focus?

It's a blood clot in your brain that will stop blood flow through that blood vessel and rapidly kill off the portion of the brain that the blood vessel is feeding.

One way of looking at it is that an ischemic stroke is like a fire. So if you start a fire, it will spread rapidly throughout the building and do damage quickly. A stroke is the same way you have a blood clot, which will prevent the movement of oxygen and nutrients. And within minutes, your brain cells are going to die. So a stroke very rapidly produces damage, the same way as a fire.

Luckily, we have this built-in safety net in our brains already. We have these specialized blood vessels called pial collaterals when we're born. The amount of these vessels you are born with can dictate how well you do after a stroke.

These blood vessels can grow rapidly and they can reroute blood back to that starving tissue, keeping it salvageable for enough time for you to get to the hospital. So we're looking at ways how we can make them enlarge and respond more robustly to the stroke.

What also makes them interesting to me is they're not just they're not organ-specific. So you have pial collaterals in your brain in the pial surface. You also have coronary collaterals in your heart. So many other organs have this type of blood vessel that we're looking at, specifically in the brain, and there's a good chance that the things we can find to stimulate these blood vessels in the brain may be helpful in other organs.

What was it that brought you to study highways in the brain?

So I had no idea I was going to be here. I didn't even think in undergrad that I would go into research. I went into undergrad saying I will be an equine or a small animal veterinarian, and research isn't my thing.

Where did you do your undergrad?

The University of Maryland, an animal sciences major, pre-vet. I knew I was going into the veterinary field, I was very direct towards being a veterinarian, and thought I'm going to go into practice.

But as part of the Integrated Life Sciences Honors College, they required that we did 240 hours of research, and I found a lab studying equine nutrition. We were out in the fields with horses, looking at golf course grasses. The idea was that golf course grasses grow slowly, so could we use those for insulin-resistant horses, where they can still be out in the field, but the grass grows so slowly that they can't eat it fast enough to get sugar to hurt themselves.

After a couple of hours, I realized this was pretty fun. We got to develop these projects to answer these questions, and I loved finding and answering interesting questions.

When I started to look at which vet school, I was advised to consider a Dual DVM/Ph.D. program. You get a bit of both sides where you can do the research, but you can still do clinics and bridge those two pieces together.

Once accepted here at the college, I connected with Dr. Theus as I thought I might want to go into regenerative medicine, and she was working on blood vessels. She started telling me about this project and it sounded amazing because it was something that was not organ-specific. So even though we were doing something in the brain, it's also related to the rest of your body. And then a lot of this is also translatable to human medicine.

What have you found most challenging during your Ph.D.?

My dad always told me, "You know, they put ‘re’ in front of ‘search’ for a reason because nothing ever works the first time." So you're doing it over and over, and you're constantly searching to answer this question. So it's just finding the resilience and the perseverance when you have a problem in your experiment, keep reassessing, looking at it to see learning from your mistakes.

I have also had an amazing principal investigator (PI) who's supportive and has given me the opportunity to do a lot of collaborations and go to a lot of conferences to present.

So you still got the research bug?

Yes, at this point, I do plan on continuing to research throughout my vet school days, and I was fortunate that Dr. Theus and I have partnered with Dr. Olsen's lab in the School of Neuroscience, and we're starting a project looking at these collateral blood vessels in Alzheimer's disease models.

How do you feel that the Ph.D. has helped you prepare for the DVM?

They are two very different degrees. The DVM is much more structured, with so much knowledge coming at you all at once. The Ph.D. is much more independently driven, and you get what you put in from it. So it's taught me a lot about time management, and it's taught me a lot about problem-solving. So two things that will translate into the DVM.

It also gave me a very wide understanding of the molecular side. I hope this will help me once I get to the clinical side, where anatomical pathology may be my future.

So tell me a little bit about getting the outstanding Ph.D. student award.

That was such an honor, and Dr. Theus was wonderful. She wrote me a beautiful nomination, and it was very much a surprise to me to win, that's for sure. Obviously, it was nice to be recognized by my PI and see that she thinks I'm doing a good job.

You also won for your recent Annual GPSS Research Symposium oral presentation. Do you like presenting?

I love presenting; it's an excellent way of explaining the work. It allows me to create analogies and different stories to explain my project. And research is very much a story, and you're trying to tell the story to others. I want it to be in a way that is as easily understood as possible because a lot of the diseases being researched can sound scary. For example, there are close to 800,000 stroke cases a year in the United States. So if you don't know somebody with a stroke, you probably will very soon. It's fulfilling and exciting work, and I love talking about my work.

So many people prefer something other than that side of presenting and talking about their work.

Growing up doing 4H and FFA, I really loved giving reasons for dairy cattle judging where you judge a set of cows and then provide reasons for placing them in that order. That exposure at a young age to a lot of public speaking made me comfortable giving public talks. I'm excited to share the work, we put a lot of time into collecting this data, and it's nice to say, hey, look, all of this time was worth something. Let's see what we did.

What advice would you give to other Ph.D. students looking to excel in their fields? And how have you developed your research skills and expertise?

Never stop asking questions because you're going to be able to build so many collaborations and also, your PI will be there as your mentor, and they will be your colleague one day as well. Having a back-and-forth conversation, I had this idea; what do you think of it? You can build off of each other, especially as you get further into your Ph.D. and you gain an even deeper understanding of the field,

So never stop asking questions and having those conversations with anyone around you, whether it's your PI, another student, a committee member, or anybody. You want to have questions because as a researcher you need a passion for answering questions. If you love the research process, it doesn't matter what question you're answering. It's the process of research that is picking a question and being able to develop ideas to answer that question. It is a lot of hard work, but there's a light at the end. You have to keep pushing.

What would you say has been the highlight of your Ph.D.?

There are quite a few, but winning this award was the most shocking. I was excited when I heard that I had won it and that Dr. Theus felt I was worthy of being nominated for it.

One of the pivotal points where I was like, maybe I am a real researcher now, was when I got invited to the International Stroke Conference to give an oral presentation. That was exciting for me, and presenting to an audience of clinicians and translatable researchers and having the questions and conversations afterward was a tremendous experience.

What are you looking forward to with the DVM program?

I'm looking forward to seeing all the different specialties and how I can relate that to research and then advance my career—trying to figure out what exactly I want to do in my future career and having those conversations with faculty members about what I need to do to get here. It's really exciting, I cannot wait.