No bands, no confetti, but still grand for the region's pets

December 1, 2020

The opening of the Animal Cancer Care and Research Center finalized the relocation of VA-MD Vet Med's oncology service from the Veterinary Teaching Hospital on the Blacksburg campus

Grand openings are usually, well, grand.

In line with these socially distanced times, however, the recent grand opening of Virginia Tech’s state-of-the-art Animal Cancer Care and Research Center in Roanoke, Virginia, was a decidedly modest affair.

Instead of a local dignitary cutting a ribbon or a popular politician delivering a rousing speech, the new clinical and research facility was inaugurated by an 11-pound domestic shorthaired cat named Kokomo, the first pet to set paw in the new center as a clinical patient.

Although Kokomo is surely more interested in batting around her favorite yellow banana toy than in cutting-edge medicine, her presence at the center, which is housed in the 139,000-square-foot addition to the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, represented the culmination of more than six years of planning.

“This center will develop and deploy novel modalities for treating a variety of cancers. We are grateful for the outstanding faculty, staff, and partners of this center that fuel its far-reaching impact,” said M. Daniel Givens, dean of the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine at Virginia Tech. “This exciting new initiative creates the opportunity for advanced, integrated cancer treatment for dogs and cats in our region and transformative, translational research that will advance cancer treatment in pets and people alike.”

Accommodating the relocation and expansion of the oncology service from the Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Blacksburg, the new facility is a vital part of the Virginia Tech Carilion (VTC) Health Sciences and Technology Campus, adjacent to the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and integrates human and veterinary biomedical researchers. The center’s faculty clinicians offer comprehensive, integrated services, including medical, surgical, and radiation oncology, and frontline cancer diagnostics and treatment for dogs and cats.

Kokomo was referred to the center to explore treatment options for a bladder tumor called transitional cell carcinoma. “When Kokomo was diagnosed in October of last year [at a clinic in Arizona], they told us she would likely only live until spring,” said owner Peter Haberkorn, who, along with his husband Aaron Betsky, adopted Kokomo 11 years ago. “She’s already exceeded expectations, so we felt like we had to give her a fighting chance.”

Patients like Kokomo and their owners aren’t the only beneficiaries of the oncology clinicians’ expertise and advanced care. The center’s unique co-location alongside human-focused clinicians and researchers embodies a true One Health approach that recognizes the dynamic interdependence of animal, human, and environmental health. Because companion animals often develop the same or similar cancers as humans, therapies developed by researchers can help human patients and serve as new treatments for pets.

“The Animal Cancer Care and Research Center here on the Health Sciences and Technology Campus in Roanoke is an important addition to Virginia Tech’s Cancer Research Alliance,” said Michael Friedlander, Virginia Tech’s vice president for health sciences and technology and executive director of the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute.

The alliance connects more than 30 researchers in Blacksburg and Roanoke into a cancer research community. Coupled with Virginia Tech’s new partnership with the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., the Animal Cancer Care and Research Center adds a new dimension: Certain cancers that occur spontaneously in pets are similar to those that occur in the human pediatric population.

“Children’s National’s new research campus in Washington, D.C., will house cancer researchers from Virginia Tech to specifically address pediatric brain cancer that shares several molecular signatures with the same type of cancer in dogs,” Friedlander said. “This is a powerful opportunity to bring together the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute’s cancer research teams, the College of Veterinary Medicine’s cancer researchers and caregivers, and multiple other cancer researchers from across the university and Children’s National programs into a unique collaborative program to advance cancer prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care for all, including families and their animal companions.”

Along with the cancer research community, the needs of Virginia Tech students are tightly integrated into the new center’s mission. Clinical services work in tandem with translational research and health sciences degree programs involving the veterinary college and the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, immersing students in a best-in-class, multidisciplinary learning environment.

For medical oncologists Nick Dervisis and Shawna Klahn, associate professors in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, who helped build the veterinary college’s oncology service in a single room at the teaching hospital in Blacksburg, the center’s opening is a dream come true. “With this team and this facility, we are ready to make a big impact,” said Dervisis.

First-in-region radiation therapy

Experiencing the new cancer center’s radiation therapy suite — nicknamed The Vault — is akin to walking onto the set of a sci-fi movie. Sounds are strangely muffled by concrete walls with an average thickness of 6 feet, special shielding, and other elements designed to allow this powerful therapy to be delivered safely. The floor alone was constructed of more than 400 cubic yards of concrete.

The Vault’s centerpiece is a $3.28 million Varian linear accelerator, one of the most advanced linear accelerators in the country and one of only a handful at veterinary institutions that meets criteria certifying it for human use.

Radiation therapy, though long part of the standard-of-care treatment options for many forms of human cancer, has never before been available to pets in Southwest Virginia. In November, the center began offering the treatment, becoming the region’s only radiation oncology service for pets.

Beyond advancing the treatment of cancer in companion animals, the center's imaging capabilities stand to provide valuable insights to veterinarians, biomedical engineers, and human medical researchers in the fight against cancerous tumors that are common to both dogs and people.

“The advanced technology in imaging and radiation therapy in our new facility has so much potential,” said radiation oncologist Ilektra Athanasiadi, an assistant professor in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences. “We are committed to pushing the boundaries through research in order to deliver even better outcomes.”

New cancer therapies

For decades, chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery have been the go-to trio of cancer treatments. But if a current slate of clinical trials at the Animal Cancer Center is successful, “bubbles” and “zapping” can be added to the list.

“One of the main goals of our lab is to defeat cancer using, yes, bubbles,” said Eli Vlaisavljevich, an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics in Virginia Tech’s College of Engineering.

Vlaisavljevich and his team have partnered with oncology clinicians at the Roanoke center for several pilot studies that use a novel technique called histotripsy, which focuses ultrasound beams to create bubbles inside a defined area. Since the technique doesn’t involve heat, damage to surrounding tissues is effectively avoided.

“To treat tumors, histotripsy can target cancerous cells with what we call ‘bubble clouds’ generated by ultrasound. The bubble clouds are made up of microscopic areas of cavitation bubbles that destroy the cancerous tissue when they expand and collapse,” Vlaisavljevich explained. Once the affected area is treated, the body’s immune system kicks in to mop up the damaged cells and, the researchers hope, stimulates an immune response that will inhibit metastasis.

At present, histotripsy is being tested in two clinical studies involving dogs. The first will use the technique to target osteosarcoma bone tumors, which are remarkably similar in humans and canines, while the second will treat dogs with soft tissue sarcomas. Although histotripsy has been studied in humans, there is little data on its use in dogs or on these tumor types.

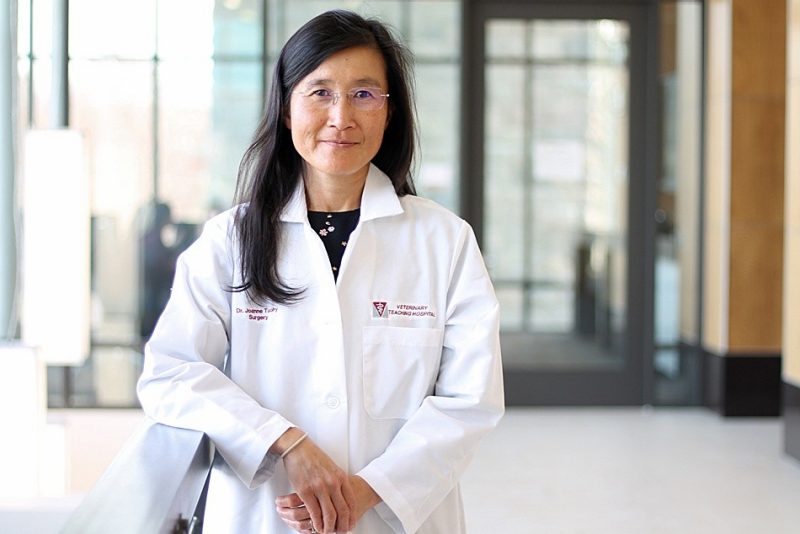

The principal investigator of the osteosarcoma study, Joanne Tuohy, an assistant professor of surgical oncology and the new center’s interim director, is excited that this technology has the potential to help humans with osteosarcoma, an acutely painful disease in both species. Over the past three decades, the prognoses for people and dogs have not improved significantly.

“Patients — both humans and dogs — need new treatments,” Tuohy said. “With the help of engineers, patients, owners, clinicians, and referring practitioners, I hope our trial can help move research forward.”

Another partnership with the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics looks to perfect a device that employs electrical pulses to kill cancer cells.

Developed by Rafael Davalos, the L. Preston Wade Professor of Biomedical Engineering, the technology called High-Frequency Irreversible Electroporation, or H-FIRE, has been refined through longstanding collaborations with faculty at the veterinary college. H-FIRE has already been used successfully in equine and canine studies across a variety of tumor types.

Dervisis recently completed a pilot study using H-FIRE in dogs with liver cancer. “Essentially, we’re zapping the tumor,” he said. “To use technical terms, we apply high-frequency electrical pulses to the cancerous tissue through a series of electrodes, which creates tiny openings in the cell membrane, ablating the targeted cells.”

In light of the success of the pilot study involving liver tumors, the oncology group has opened a new round of clinical trials, expanding the number of canine patients and the types of tumors to be treated. The current studies are focused on pancreatic, brain, and lung tumors, all cancers that can be difficult to treat in both humans and dogs.

A top-to-bottom approach to chemotherapy safety

The importance of personal protective equipment and proper ventilation has become a familiar refrain during the COVID-19 pandemic. For researchers at the Animal Cancer Center, however, safety protocols for handling potentially contaminated materials and preserving indoor air quality have long been the order of the day. These protocols are, in fact, woven into the very fabric of the new facility.

It’s universally known that chemotherapy can be hard on a patient’s body, causing such side effects as gastrointestinal problems and fatigue in both people and animals. Less frequently acknowledged is the potential harm that chemotherapy can have on those who administer it.

“Compared to the kind of high‐dose exposure that cancer patients receive,” Klahn said, “research has shown that chronic low-level exposure to chemotherapy actually may have increased risk for the people who administer it.”

In response, Klahn and six other experts nationwide spearheaded an effort to raise awareness of the potential dangers surrounding the use of chemotherapy drugs in veterinary medicine. In 2019, the group drafted a consensus statement for the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Drawing on that expertise, Klahn worked closely with the Roanoke center’s construction team to ensure that the chemotherapy-delivery suite meets stringent safety guidelines.

The purpose-built space includes such features as special air-handling, an advanced biosafety cabinet, a three-room chemotherapy suite, and a secure hazardous waste disposal stream, making the center a national model for the safe handling and administration of chemotherapy.

Even as the space’s built-in features are crucial, the center’s highly skilled faculty and staff realize that ongoing training and adherence to policy set the facility apart.

This conscientiousness is the lynchpin of the center’s chemotherapy safety program. “We have policies for everything: administration and delivery of chemo, storage and disposal of drugs, discharging pets, even educating owners on how to safely handle pet waste,” Klahn said. “We share responsibility for modeling good practices.”

The people in the fight: New faculty, interim leadership, a new director on the horizon

Treating veterinary cancer is not for the faint of heart. Pets’ shorter lifespans, coupled with the inherent lethality of many cancers, makes oncology a specialty that attracts those who are motivated to fight long odds. And for many clinicians and researchers, more of the same is just not good enough.

“The cancers I focus on in my research have some of the direst prognoses in veterinary medicine. Many of these cancers, like osteosarcoma and pancreatic tumors, are also very aggressive in humans,” said Tuohy, who is exploring new therapies for these deadly tumors. “The survival expectation of dogs and people with osteosarcoma, as one example, hasn’t improved in decades. It’s such a painful cancer for patients and often highly metastatic.”

In the face of such bleak prognoses, Tuohy still believes that abstract questions are less important than the lives of her patients. “I think it’s important to hold on to the positive outcomes,” she said, “but also remember the cases where things didn’t go well. We have to do that if we’re going to improve outcomes.”

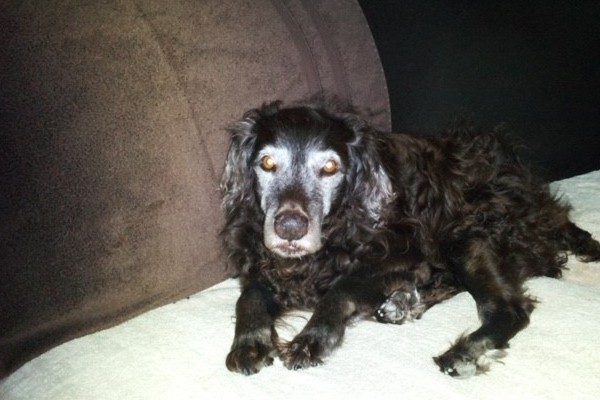

Tina Pegg, the owner of Bradford, an 11-year-old mountain cur mix, shares Tuohy’s outlook.

Bradford, a protective, quirky dog that, Pegg said, “just showed up” right before Thanksgiving in 2011, had a big personality. Diagnosed with a pancreatic tumor that metastasized to a lymph node, Bradford recently died after undergoing an experimental procedure on the tumor.

Although the outcome wasn’t what was hoped for, Pegg understands the value of Bradford’s treatment. “Bradford was a trailblazer. He did what he had to do to contribute [to the advancement of science], and then he was ready to move on,” said Pegg. “I truly believe this was the right path for him.”

As the new center’s interim director, Tuohy is surrounded by a team that shares her commitment to improving outcomes for animals like Bradford. Joining Athanasiadi, Dervisis, and Klahn, three new veterinarians were recently hired, expanding the ranks of the 11 doctors, six technicians, and four staff members who support the center’s operations.

Radiation and medical oncologist Keiko Murakami has distinctive credentials, having completed two demanding residencies: one in radiation oncology at Purdue University, and one in medical oncology at Auburn University.

Oncologic surgeon Brittany Ciepluch completed an internship at the University of Florida, a residency at Texas A&M, and a surgical oncology fellowship at Colorado State University.

Nick Rancilio, a radiation oncologist and researcher who arrived from Auburn University, focuses on stereotactic and hypofractionated radiation therapy, techniques designed to deliver precisely targeted radiation in fewer treatments.

In addition, a search for a permanent director to lead the growing team of cancer experts has been opened. “We’re hoping,” said Tuohy, “to find someone who is passionate about advancing the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer in pets, as well as promoting the principles of One Health to achieve progress in cancer care for animals and people.”

Well prepared in the face of difficult and sometimes emotionally painful work, the oncology team at the Animal Cancer Center is committed to uncovering ways to extend and improve the quality of their patients’ lives. Like Tina Pegg’s description of her dog's journey, they, too, believe they are on the right path.

— Mindy Quigley is clinical trials coordinator in VA-MD Vet Med’s Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences.